ENNIE MAKHAFOLA AND TSHEGOFATSO MASHABELA | Our clinics are not border control

Guest contributor

29 September 2025 | 10:20"We do not dismiss the frustrations of communities who feel abandoned. We share them. Public services are stretched to the limit. But the way to resolve them is by pressing the responsible authorities to do their jobs."

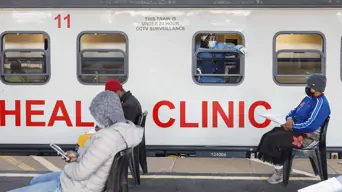

A nurse for Transnet-Phelophepa Healthcare Train points out the window as patients sit in a queue at the Dube Station in Soweto, on June 22, 2021. The Transnet-Phelophepa consists of custom-built trains that deliver primary healthcare to remote areas of South Africa. Picture: Phill Magakoe / AFP

In recent weeks, we have found ourselves at the gates of clinics where unauthorised groups of people have taken it upon themselves to demand identification documents from patients before they may enter.

They have gone as far as harassing South Africans, forcing them to produce ID books or cards to access basic care.

It is a sight that evokes painful memories of the Dompass humiliations under apartheid. Ordinary people, black and poor, queuing with papers to prove their right to exist, this time not for entry into workplaces but for entry into health facilities.

This is not only unlawful; it is dangerous. Our clinics are not border posts. Nurses and doctors are not immigration officers. Yet what we are seeing is a creeping attempt to turn the frontlines of public health into checkpoints for citizenship. There may be some of us celebrating this now, but it is a seed of something that will have devastating effects for future generations if not handled with necessary care.

We know this because of what happened in Alexandra in 2005 and 2008.

But wemust start from what everyone accepts. It is common cause that South Africa has a problem of undocumented migrants. Some are in the country without papers. Some have documents obtained through fraudulent processes. Some have valid and legal documentation. It is also true that document fraud is not confined to poor migrants from neighbouring states.

Some of the worst abuse involves well-resourced individuals, including Europeans who have bought false papers. It is also common cause that big companies deliberately hire undocumented workers. They do this because undocumented workers are easier to exploit, willing to accept very low wages, and unable to organise without fear of deportation.

These realities are challenges we do not deny, and no one can accuse South Africans of unjustly complaining about challenges brought about these challenges.

They have a real effect on jobs, wages and the planning of public services.

When clinics cannot know in advance how many people will seek care, it is difficult to allocate staff, medicines and budgets accurately

This strain is real. But it cannot be resolved by refusing a sick or injured person medical treatment. None of the facts about undocumented people justify denying a human being care in their hour of need.

They point instead to failures of immigration management and labour enforcement. Those failures must be fixed by the authorities responsible for them: Home Affairs, the Department of Employment and Labour, the South African Police Service. They cannot be dumped onto a nurse at a clinic reception.

South Africa’s Constitution is explicit: “No one may be refused medical treatment.” There is no footnote or qualifier that limits this to citizens. “No one” means exactly that—every person on South African soil. The National Health Act repeats this duty for every health worker and every health establishment. These are binding laws, not optional guidelines.

The South African Human Rights Commission has made clear that immigration status does not remove this right. Any attempt to rewrite Section 27(3) to add a demand for passports or IDs at casualty doors would be unconstitutional. It would also be a direct attack on the values of dignity and life at the heart of our Bill of Rights.

South Africa’s approach is not unusual. It is consistent with international standards. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has confirmed that the right to health must be guaranteed without discrimination of any kind, including on the basis of nationality or legal status.

The UN Convention on the Rights of Migrant Workers is even clearer: migrant workers and their families have a right to urgent medical care, and such care “shall not be refused… by reason of any irregularity with regard to stay or employment.” The African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights requires states to ensure medical attention when people are sick.

The World Health Assembly, the decision-making body of the World Health Organization, has called on all countries to ensure equal and non-discriminatory access to healthcare. And the UN’s commitment to Universal Health Coverage makes the same point: healthcare must be accessible to all, without discrimination.

What does it mean in practice if South Africa abandons this principle and chooses instead to say “no proof of citizenship, no care”? It is not an administrative tweak. It means that ambulances and casualty staff will have to stop and check documents before treating a stroke, a heart attack, a haemorrhage, sepsis, or a serious injury.

People will die in the time it takes to photocopy an ID. It means that nurses and doctors, trained under oath to save lives, will be forced to act as immigration officers, undermining their ethics and their duty of care.

It means that people with communicable diseases, such as tuberculosis or other serious infections, will delay seeking help for fear of being turned away, increasing risks for the wider community. And it means opening the door to vigilante behaviour inside hospitals—normalising unlawful intimidation and violence in the very places where people come for healing.

South African courts have been clear that “emergency medical treatment” means intervention in dramatic and sudden conditions that are time-critical. Any delay to check passports at clinic doors defeats this purpose and is unlawful.

If the aim is to manage immigration and protect jobs, then let us be honest: the solutions are not in the casualty ward.

The solutions are:

• Fix immigration administration by resourcing Home Affairs, speeding up lawful documentation and modernisingidentity systems.

• Enforce labour law by inspecting known sectors of abuse, penalising employers who hire undocumented workers to drive down wages, and protecting whistle-blowers.

• Keep health separate from immigration. Treat first, record basic details, and handle immigration issues later through proper channels.

• Invest in emergency care by setting national standards for ambulances and casualty departments so facilities can cope with demand while respecting the Constitution.

Anything less is a betrayal of our constitutional order.

We are also deeply concerned about the rise of unauthorised groups patrolling hospitals and clinics, demanding IDs, and threatening staff and patients. This is unlawful. It is vigilantism dressed up as patriotism. It is dangerous, because once we allow people to take the law into their own hands at clinic doors, we will not be able to draw the line elsewhere.

Our countryhas a proud history of civil society mobilisation that has made real change without stepping outside the law. The Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) confronted government and forced it to provide antiretroviral treatment, saving millions of lives. OUTA has held government accountable in the courts. These movements succeeded by using facts, the Constitution, and public pressure - not by wearing paramilitary uniforms or intimidating sick people.

We do not dismiss the frustrations of communities who feel abandoned. We share them. Public services are stretched to the limit. But the way to resolve them is by pressing the responsible authorities to do their jobs.

We are ready and prepared to march side by side with anyone who will go directly to the Minister of Home Affairs and to the President to demand proper border control, efficient immigration processes, and fair documentation of all people in South Africa. That is where the solution lies, not in humiliating patients at clinic gates.

The proposal to revise Section 27(3) so that emergency care isonly afforded to people who can prove citizenship or legal status would be unconstitutional in South Africa, contrary to the National Health Act, out of step with the African Charter, the WHO and UN standards, and would lead to unnecessary deaths and public-health crises. The Constitution’s guarantee must stand as it is. Let us fix immigration systems and labour enforcement where the problem truly lies, and keep health as health.

Ennie Makhafola is a qualified registered nurse and the MMC for Health and Social Services in the City of Johannesburg, and Tshegofatso Mashabela is the MMC for Health in the City of Tshwane. Both serve as councillors for the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF)

Get the whole picture 💡

Take a look at the topic timeline for all related articles.