BOOK REVIEW | 'Burning down the house': A Feminist call to rethink home, power and gender violence

Jamil F. Khan

12 November 2025 | 9:26'As a metaphor for dismantling gender hierarchies, Burning Down the House is a powerful attempt to ask the questions that help us rethink our homes as sites of gender reproduction.'

Picture: Pixabay.com

South Africa has long been known as one of the femicide and rape capitals of the world.

Many well-informed observers have attributed this to better reporting systems compared to countries where rape and femicide rates may equal or exceed ours but remain vastly underreported.

What is not up for debate, however, is that we experience unconscionably high levels of gender-based violence, of which rape and femicide are alarmingly prominent features.

The violence that women, children and queer people face is most often perpetrated by people they know and frequently takes place within the home.

In our imagination of how society works, most would designate the home as a safe space, where one is protected from external threats.

However, the very idea of “the home” is built on the politics of gender and the power imbalances that define the nuclear family unit we are taught to aspire to.

Understanding this requires us to re-examine our assumptions about the home as a space insulated from the wider societal politics atplay.

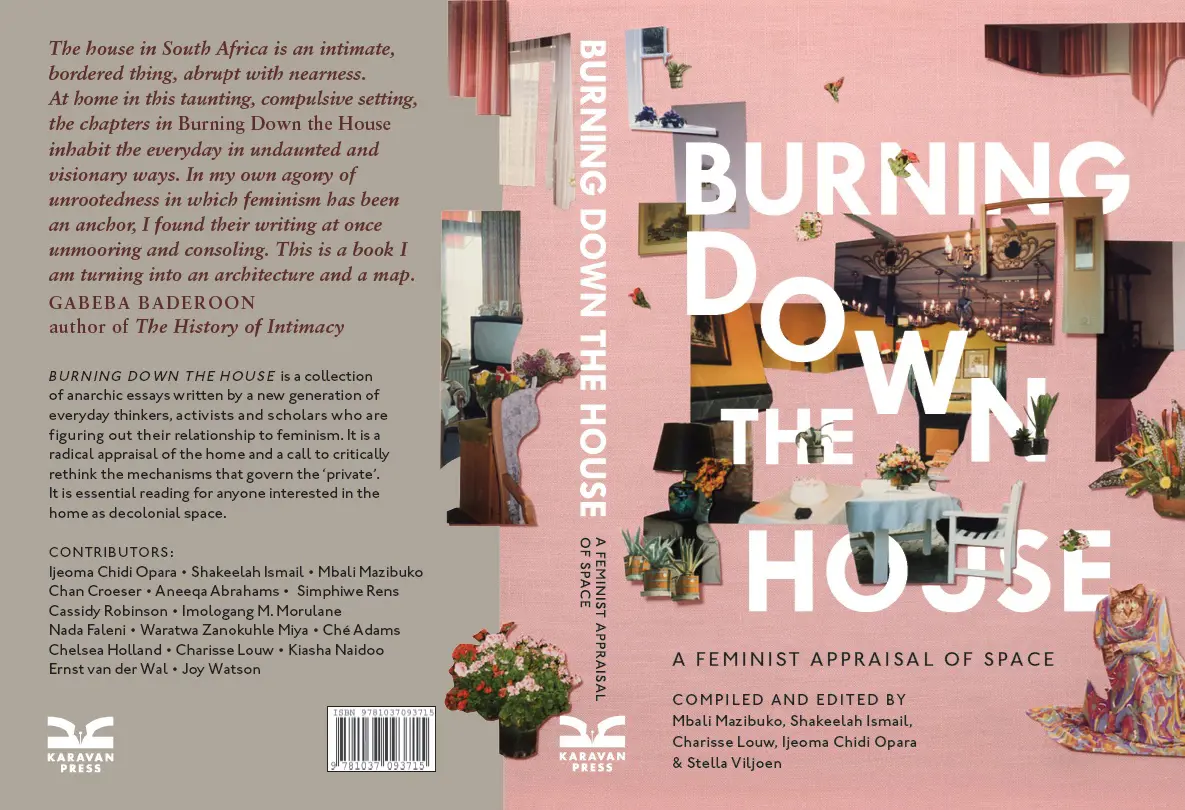

To this effect, a new book, Burning Down the House, offers a feminist appraisal of space that asks us to consider how gender norms have shaped the spaces we call home, and how home serves as a mirror for the society we live in.

Compiled and edited by Mbali Mazibuko, Shakeeelah Ismail, Charisse Louw, Ijeoma Chidi Opara, and Stella Viljoen, the book “is a collection of anarchic essays written by a new generation of everyday thinkers, activists, and scholars who are figuring out their relationship to feminism. It is a radical appraisal of the home and a call to critically rethink the mechanisms that govern the ‘private’.”

Through feminist explorations of home spaces, the contributors compel us to confront generational shifts in the demands made by women and queer people to eradicate gender oppression in all spheres of existence.

As one moves through the chapters, it uickly becomes apparent that the reader is intellectually exploring various homes and home spaces that are not simply physical buildings, but embodied spaces defined by the lives lived within them.

The lives lived in the average home continue to be, just as they have historically been, highly regulated by the rules of binary cis-heterosexual gender, making feminist inquiry into the home imperative.

Through the intersectional analysis offered by the contributors, the gender question driving the book is deeply intertwined with issues of race, sexuality, class, culture and body politics, making it “essential reading for anyone interested in the home as a decolonial space.”

Burning Down the House is much more than an intellectual exercise; it makes a tangible contribution to the fight against gender-based violence by donating all proceeds from its sales to Women For Change and their tireless efforts to combat GBV.

The work of Women For Change has placed the nation’s grievances at the forefront, having delivered a petition to the Union Buildings seven months ago in protest of femicide numbers that saw 5,578 women murdered in a single year.

The organisation’s relentless advocacy has not come without resistance and the familiar sense of dismissal that often arises when activists challenge the status quo.

Undeterred, Women For Change has persisted, coordinating a campaign designed to draw attention to this national crisis through the G20 Women’s Shutdown, which calls on “all women and members of the LGBTQI+ community across South Africa to refrain from all paid and unpaid work, and to spend no money for the entire day to demonstrate the economic and social impact of their absence.”

The shutdown, set for 21 November, is strategically aimed at disrupting the government’s performance of efficiency for visiting heads of state, making the point that “until South Africa stops burying a woman every 2.5 hours, the G20 cannot speak of growth and progress.”

This past week, social media has been awash with purple as people change their profile pictures and post status updates with purple hearts to commemorate lives lost to gender-based violence and to raise awareness of the campaign’s demands. While this campaign is an organisational initiative, it is owned by all of us who should be working to dismantle the inherited frameworks of gender oppression that have been normalised.

While the task may seem insurmountable, it requires multi-layered approaches that begin with rethinking our belief systems and questioning how gender operates in our everyday spaces.

As a metaphor for dismantling gender hierarchies, Burning Down the House is a powerful attempt to ask the questions that help us rethink our homes as sites of gender reproduction. Using fire as a metaphor for the destruction and dismantling of gender oppression, the book calls on us to recognise how commonplace patriarchal violence is.

Fire becomes both a tool of persecution and of retaliatory rage: women, femmes and queer people have faced the fire for centuries, from the women of Europe and the United States burned at the stake as “witches” for resisting patriarchal control, to our present South African reality where women and queer bodies are found in fields and car boots after patriarchal rage has ended their lives.

We face the fire. We know the fire. And we can command the fire. That is what this book does, in myriad ways, reminding us that our feminisms, however differently informed -demand that we answer the question: how did we get here, and where to from here?

The work being done to resist the normalisation of gender-based violence is commendable, but it requires everyone’s support. Our attitudes towards gender-based violence must change, and that change begins with our beliefs. While many answers lie at the top, just as many lie around us - within our living rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, and bathrooms.

Our interrogation of these matters cannot be shallow. When we look at one another, we must remember that our experiences of the rooms in patriarchy’s house are shaped by different circumstances, especially in the wake of a highly stratified, apartheid-made society. The task may be immense, but the changes we seek are already in motion and calling on all of us to step aboard.

Dr. Jamil F. Khan is an award-winning author, doctoral critical diversity scholar, and research fellow at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study.

Get the whole picture 💡

Take a look at the topic timeline for all related articles.