JAMIL F. KHAN | 'Our queer community is not for sale': The fight to reclaim South Africa’s radical queer legacy

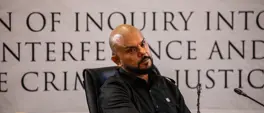

Jamil F. Khan

22 October 2025 | 6:36"Those who choose to validate a capitalist retelling of our resistance in a country where economic sanctions and boycotts directed at corporations contributed significantly to toppling apartheid must speak for themselves, and their shallow individual interests."

Picture: Pixabay.com

October is officially Pride Month in South Africa. Although the global reach of American politics draws the whole world into celebrating heavily contextual histories as universal, this is the month that South Africans commemorate the first Pride march which took place in 1990.

Understood through the available language of the time, the fight for gay and lesbian rights to be recognised as human rights included an intersectional struggle that made the march an anti-apartheid struggle too.

Activists such as Bev Ditsie, Simon Nkoli, Peter Busse and Linda Ngcobo, who founded Gays and Lesbians of Witwatersrand (GLOW) made it very clear that they “refused to allow GLB issues to take a backseat to democracy and anti-apartheid processes”, making sure that Pride in South Africa meant a rejection of all forms of domination and exploitation, here and elsewhere.

The city of Johannesburg then became the centre of this resistance, where we still celebrate Joburg Pride around the same time every year. As a gift from those leaders, and many others, South African Pride traditions have anti-apartheid activism built into them and refuse the normalisation of colonial, imperial ideologies that relentlessly try to co-opt resistance movements and silence their fury by seducing them with capitalist pinkwashing strategies.

Far from its origins in anti-apartheid struggle, Joburg Pride has been at the centre of controversy for years following a 2012 protest by Black lesbian and gender non-conforming protesters to bring attention to the disproportionate homophobic violence experienced by Black women in South Africa’s townships.

While asking for solidarity at a march meant to protest queer oppression, the protesters, part of the One in Nine campaign, were met with racialised violence and were instructed by the organiser at the time to “get off my route” instructing the drivers of a fleet of sponsored Mercedes-Benz’s to “run over them” if they did not move.

This tragic event led to the splintering off of political interests that formed Joburg People’s Pride, Ekhuruleni Pride and Soweto Pride as alternatives to what has become a celebration and encouragement of middle-class collaboration with corporate capital. This delivers a thoroughly blunt instrument of protest that now only protests the inconvenience of having to face the apartheid of economic and social inequality that still harms poor, Black queer people.

This shift was demonstrated in 2018, when the Pride organising committee led by Kaye Ally, hosted a lifestyle conference which furthers the organisation’s interest in moving from hardcore activism to advocacy with a more celebratory tone.

In an interview with researcher Dan Conway for an article titled: “Whose Lifestyle Matters at Johannesburg Pride? The Lifestylisation of LGBTQ+ Identities and the Gentrification of Activism” Ally notes that their aim is to cater to “members of the LGBT community [in South Africa] who are quite comfortable, blacks, whites, Indian, coloured . . . expat. Quite regular.

Comfortable. Normal! Professional. Two- income households, fancy houses, fancy holidays. Adopting children, getting married, going out to dinners. Very, very normal lifestyles!” This “target market” intersects quite conveniently with the interests of the organisation’s corporate sponsors rabid for pink Rands. As Conway notes: “the Lifestyle Conference identifies ‘whose lifestyle matters’ in relation to a nexus of corporate, media and LGBTQ+ interests in South Africa and, by omission, whose does not.”

This year, Joburg Pride has onboarded Amazon as a corporate sponsor. Amazon is well known for supporting apartheid Israel, building its African headquarters on sacred natural sites and capitulation to Donald Trump’s anti-DEI agenda. In response a collective of individuals and organisations operating as “NoGoBurg Pride”, an alternative gathering, has written an open letter to Joburg Pride noting that:

“We are in a scary time of neoliberal capitalist appropriation; right wing violence; and oppression of black indigenous, queer people and territories by colonial-capitalist and patriarchal forces.

By making Joburg Pride a space focused on corporates and the most privileged, Joburg Pride becomes a mockery of our so-called intersectional rainbow country, missing the colour black. The awareness of class, race and capitalism is sorely non-existent in this non-purposeful Pride. We are saddened that this Pride has become nothing more than a sponsored party - selling corporate products and rainbow-washing the image of companies.”

Joburg Pride’s great push this year centres on visibility of the queer community, but whose visibility? As this conversation proceeds on Instagram, one comment denouncing this response as a smear campaign attempting to rewrite the purpose of Pride and turn it into a battleground of foreign policy, caught my attention.

The poster further suggests that because anti-queer legislation in Middle eastern countries oppresses queer people, our activism for queer liberation here should not include denouncement of the genocidal erasure under Israeli occupation, since we have our own problems at home. Another exclaimed: “leave us out of it”.

This view permeates some spheres of South African society where a self-interested logic dismisses struggles seen as external to ours. Ironically, in the case of Pride this year, this spineless, sycophantic defence of complicity with deadly corporate interests is a result of the very capitalist thinking it tries to redeem.

Another thread of capitalist thinking suggested here is that we should only care if we are getting a “return on investment”, making an appalling case for transactional humanity. As noted by Ally in the interview with Conway above, Pride has gone “beyond human rights” choosing instead to focus on queer (heteronormative) lifestyle ambitions making it completely incompatible with the ethos of collective humanity and our responsibility to resist oppression everywhere, until we are all free.

It is clear that Joburg Pride and its proponents have abandoned all frameworks of anti-apartheid resistance that compel us as human beings, and South Africans to insist on justice, not only for a few, but for all.

If we truly accept that our struggles can be neatly sanitised of connection to global struggles for freedom from colonial, capitalist structures of domination for the sake of pretty optics, then we have lost our voice of moral authority on the matter of apartheid.

Far from an overwhelming majority, those who choose to validate a capitalist retelling of our resistance in a country where economic sanctions and boycotts directed at corporations contributed significantly to toppling apartheid must speak for themselves, and their shallow individual interests.

At the heart of Black queer resistance has always been an unwavering sense of community and solidarity work across oppressed groups. Those who want to collaborate with our shared oppressors must do so in their own names, without co-opting the sense of community we formed in opposition to the isolating individualism championed by capitalist thought. Our queer community is not for sale!

Jamil F. Khan is an award-winning author, doctoral critical diversity scholar, and research fellow at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study.

Get the whole picture 💡

Take a look at the topic timeline for all related articles.

Trending News

More in Opinion

6 March 2026 13:15

MALAIKA MAHLATSI | Rand Water is fighting a losing battle in Gauteng: This is why

6 March 2026 11:30

CHARLES MATSEKE | Overconfident, Over-Privileged, Over-Experienced: The Paul O’Sullivan Paradox

6 March 2026 11:10

JUDITH FEBRUARY | District Six at 60: Remembering forced removals and Cape Town's unfinished healing