VUYANI PAMBO | Biko, Bonga, and the running waters of Gauteng: Towards a liberation theology for South Africa's 2026 Elections

Guest contributor

18 February 2026 | 17:30The African National Congress government is not merely failing to deliver water, writes Vuyani Pambo.

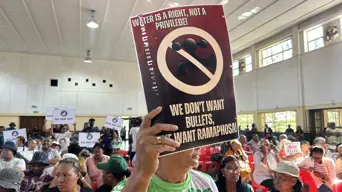

Coronationville and Westbury residents meet with Joburg Water and mayor Dada Morero over water challenges. Picture: Jabulile Mbatha/EWN

I recently had the good fortune of spending a morning with Father Bonga Mkhize, a priest at the St. Peter Claver parish.

He spoke with such measured conviction of servitude, not as a tool of subjugation, but rather as an opportunity to recalibrate the way we relate to our community.

To serve, he said, is not merely to act charitably; it is to see the face of God in the one who is thirsty. I walked away from that morning session inspired by how the priest radically interpreted the gospel.

Driving from Pimville to Diepkloof quickly made me realise how what I witnessed stood in stark, agonising contrast.

Men, women and children chasing after a passing water truck. It made me brutally reflect on the incompetence of those who are meant to serve us.

When Gauteng Premier Panyaza Lesufi expressed his solidarity with the waterless residents by pointing out that just like them, he suffers when there is no water and is at times forced to use a hotel to take a bath, the man did not intend to offend. And from where I sit, that is precisely the problem.

The irreverent African Literature Professor James Ogude would often remind us that offence is not in the malice but rather in the absence of it. To this end, there is nothing cruel in what the premier said; there is only an emptiness where an understanding of power ought to reside.

I am aware that the premier has since issued an apology, but I could not help but think of Ousmane Sembène's devastating satire, Xala.

The film depicts a post-independent Senegal, where the new leaders are afflicted with a curse: the xala or umkhokha.

This curse appears on their wedding nights. They can govern, but they cannot consummate. This then is to say, the likes of Lesufi or even Water and Sanitation Minister Pemmy Majodina, who occupy offices in the Union Building, are unable to deliver the fruits of the liberation.

This, then, to reference Tsitsi Dangaremba, is our nervous condition.

The African National Congress government is not merely failing to deliver water. It has become an administration that is afflicted by a curse of incompetence to the extent that, while water fails to run through taps from Soweto to Midrand, our premiers only worry about hotel bookings.

Wole Soyinka once wrote that the ultimate test of a people’s freedom is not the flag that flies over parliament, but the availability of water in their villages. Steve Biko understood that the first act of liberation was psychological: the colonised mind must first reject the premise that it deserves to be colonised.

Frantz Fanon, in the final passages of The Wretched of the Earth, warned that the national middle class, which replaces the colonial administration, often becomes its successor in everything but name.

These are not philosophers speaking in abstract terms, but rather serve to remind us of the diagnosis of our present tense.

Just recently, I attended the so-called SONA, where politicians dressed to the nines, strutted the red carpet, and in their comfortable poses for cameras, seemed to have mistaken proximity to power as a stand-in for service to the people. It is as if making yourself visible, wearing reflector jackets at empty reservoirs, is a substitute for service delivery.

Father Mkhize’s words returned to me as I watched residents queue up for the water truck.

Servitude, in the biblical sense, is not the performance of occasional charity. It is the complete re-ordering of one’s life around the needs of the other.

It is the belief that my baptism obliges me not to merely pray for the thirsty, but to dismantle the systems that keep them thirsty in the first place.

I am tempted to draw upon the experience of the woman at the well, but allow me to digress.

Ever since I was a child, I have recited the Lord’s Prayer so often that its radicalism has been eased away by familiarity.

I am certain that for many of us, we have grown accustomed to reciting it, but without giving due thought to what we are saying, or even what we are asking for.

But to read the prayer through the lens of liberation theology, it soon becomes clear that each petition is not just an ordinary demand, but a revolutionary one.

“Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.” This is not a request for the day when, as they say in IsiXhosa, “sesiwele umlambo”.

No. Rather, it’s a demand that the distribution of water, land, bread, and dignity reflect the justice of God. The kingdom is not an abstract land far, far away, but rather what life on earth should look like when the poor are fed, and the powerful are humbled.

“Give us this day our daily bread.” The Greek word, epiousios, suggests not merely bread for today, but bread for the coming day.

This reminded me of Father Mkhize statement that as a priest, whatever is given to him, he must share with others daily. Thought of differently, the idea of sharing with others, of epiousios, is a rebuke against neoliberal economics, which has at its center the idea of cogito, ergo sum (I think therefore I am).

The epiousios in the African context is that “I think, therefore we are, since we are, therefore I am”.

Hence, the prayer underlines the collective, for I cannot be well if my neighbour lacks water.

“Lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil.” For the longest time, most of us have understood this at a personal level, but have neglected to read it through the purview that challenges the seduction of power without accountability. It is the belief that the ends of liberation justify the means of corruption.

Simply put, it is as if we could shout to the heavens, “oh’, yhini Bawo,”, deliver us from leaders who shower in hotels while their people are forced to wash in tears.

As I write this, the water crisis still continues unabated. The tragedy is that it will continue until we, the leaders of this generation, repent of our xala, our curse of impotence disguised as power.

We must descend from the hotels of our comfort and stand in the queues with our people. And we must resolve that, come 2026 local elections, we will neither seek nor support any candidate who cannot recite the Our Father and mean it as a political programme.

Why? Because the kingdom of God is not coming on clouds of glory. But I dare say that it will come through pipes that work, taps that flow, and leaders who understand that the only legitimate power is power in the form of a servant. May we have the grace to recognise it and the courage to vote for it. Amen!

Get the whole picture 💡

Take a look at the topic timeline for all related articles.

Trending News

More in Opinion

13 February 2026 10:24

JAMIL F. KHAN | Crime is not the disease, it’s the inheritance

13 February 2026 04:28

MANDY WIENER | Ramaphosa meets the moment on water and crime, but lived experiences will be the measure

12 February 2026 09:49

JUDITH FEBRUARY | SONA 2026: Ramaphosa faces a defining test of leadership and the rule of law